Next to the boy, on his own, is a far more serious gentleman. A watch is in his hand. Fond of new-fangled things and of accuracy, he doesn’t waste time. He measures it. How long will it take before the creature in the glass bowl loses consciousness? This is important stuff. And he will not be persuaded of anything unless it can be proven and demonstrated clearly. Maybe he will go home and write it all up in his diary. He could be an academic, a local doctor, a teacher or a gentleman farmer, someone used to dealing with creatures and their needs – air being a new one to add to the list.

This is the age of the Enlightenment, after all. Technology, for him, is preferable to faith. And you can feel important if you understand these things and can speak about them with authority.

But not everybody in the painting is so dispassionate. It's time to take a close look at the figures to the right: the two young girls in the company of what would probably be their father, and a single gentleman seated to the side.

The two young girls

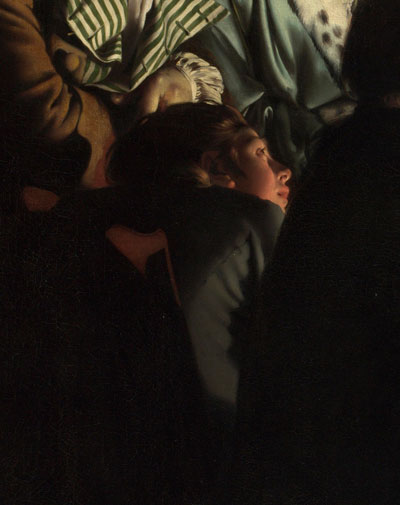

The two girls might be sisters - and quite well-to-do young ladies, as well, with their silks gowns and strands of beads or pearls in their hair. Derby, at the time, was an important centre for silk weaving, and the little sashes of blue silk around the waist and as headband of the eldest are beautifully rendered. The girls are, however, clearly moved and upset by what is taking place. And it's not simply a matter of squeamishness among those who have led sheltered lives. It is a genuine distress - a sentiment that would have been very much shared by adults at the time.

Too shocking

If this sounds peculiar, we should take note of the words of Scottish astronomer James Ferguson. Most likely an acquaintance of the painter, Ferguson was one of the men who used to stage demonstrations of this kind himself. Only, he would use a small air-filled bladder at the focus of his experiment instead of a live bird. He said that the use of a living creature for such a purpose was ‘too shocking to every spectator who has the least degree of humanity.’

These words, remember, are voiced in a period where bear-bating or public executions are still common forms of entertainment! What we today would consider cruel was to the Georgians perfectly acceptable. In this conterxt, those who showed themselves to be dishonourable or dishonest were ripe for punishment, while those creatures who were inherently brutal or violent, bears, dogs, foxes, and so on, were candidates for the horrors of the ring or the hunt.

But there were notable exceptions. God’s fairest creations, uncorrupted and in their innocent state, were different. The meek of the world: birds flowers, children, and so on, were to be venerated (and still are, of course). Thus, the two girls resonate with the creature in the glass bowel because of their shared innocence and naive simplicity. The suffering of the bird is their suffering, and also that of everyone else present, whether they know it or not.

The father