Return to the North

Although these few short years in the south appear to have been a commercial success, he returned to his native north soon enough. And here he remained at his beloved Knostrop until his death in 1893. Agnes, still resident, died a little earlier in 1890. His wife Frances survived them both, however, passing away in 1917. By then Grimshaw’s important contribution to the story of Victorian art was assured. And among his children, four had already become painters in their own right.

Today, his work can be seen in galleries as far afield as: Bradford; Gateshead; Halifax; Harrogate; Huddersfield; Hull; Kirklees; Leeds; Liverpool; London’s Tate and the Guildhall Art Gallery; Preston; Scarborough; Wakefield; Whitby; Hartford; Kansas; Minneapolis; New Haven; New Orleans; Rhode Island; Victoria and Port Elizabeth.

Technique

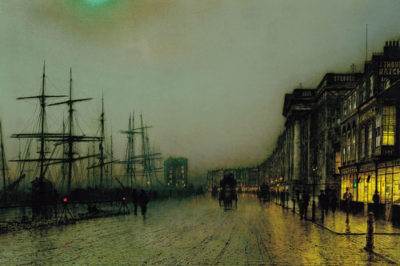

Of course, Grimshaw’s paintings are not everyone’s cup of tea. Dark in tone. Heavy in sentiment and populated by brooding figures set before tall Gothic buildings or lost in vast city streets, they can be perceived as being rather … well, grim. In his day, he also attracted a fair bit of opprobrium due to his extensive use of photographic sources for reference. Rumours were that he projected photos onto blank canvases and sketched in the outline of buildings and trees. It is even thought that in some cases he may have worked directly onto a photographic underlay, building up the paint on top of the image. All this was tantamount to practising the dark arts in the conventional art establishment of the time.

Close-ups showing detailed outlines in black – is it paint or pen & ink?

His work also combined different mediums – such as, what looks to me in some instances, to be pen and ink outlines with thin washes of paint on top. Sometimes, it is almost as if he uses oil paint like watercolour. Even at the time, his critics complained that it was difficult to detect brush strokes or textures. Though, contrary to this, he is also said to have mixed sand into his paint to create effects. In other instances, he applied the paint so thinly that the texture of the canvas showed through, adding a certain sparkling effect.

Romanticism

His emotionally intense approach was completely compatible, however, with the wave of Romanticism that was sweeping Europe at the time. There was a resurgence in interest in medieval and legendary history; in Gothic architecture and Romantic poetry. There were the novels of Dickens. And the music of the great German composers such as Brahms, Schubert and Wagner were hugely popular in late-Victorian England. John Atkinson Grimshaw was part of this great cultural and artistic milieu, giving visual form in his landscapes to so much of that glorious self-indulgent culture of the grotesque that we call ‘the Gothic.’

John Atkinson Grimshaw, At The Park Gate, 1878.

Conclusion and a video

In a sense, Grimshaw’s work is as inscrutable as the man himself. An enigma. He left little evidence of his personal life to posterity. No letters, no diaries, and very few documents of any kind. Does it matter? I for one have always loved his work. His landscape is one in which many a writer’s imagination flourishes.

Finally, as a little tribute, here is a video containing some of his most evocative paintings.