Elizabeth would have been perfectly happy for the spectator, to compare her to Aeneas. Although male, he was an individual who also famously overcame temptation in love. In his case this was the queen of Carthage, Dido. Aeneas resisted her charms. On orders from on high (the god Jupiter), he abandoned poor Dido (who took her own life as a consequence) and went on to command the destiny of a powerful nation. Aeneas sacrificed love, in other words, for the good of the people. And as early as the first full year of her reign - 1559 - Elizabeth had made it abundantly clear in her first speech to Parliament that - much to their horror - she was prepared to do the same.

'... in the end this shall be for me sufficient, that a marble stone shall declare that a Queen, having reigned such a time, lived and died a virgin.'

Marriage proposals

At the time of this wonderful painting Elizabeth had just emerged unscathed and unwed (which to her might well have meant much the same thing) from the latest bout in a lengthy courtship. This was the marriage proposal from Francis, Duke of Alençon (see ‘Elizabeth – the Virgin Queen and the Men who Loved Her’).

Francis, Duke of Alençon.

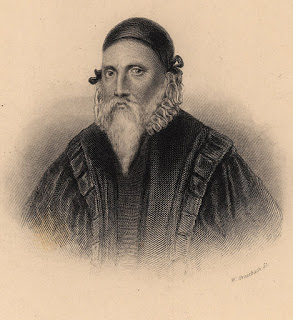

Being a Frenchman, Alençon was regarded with mixed feelings among Elizabeth’s Privy Counsellors. Some were in favour. Others not so keen. Among the detractors, moreover, was the possible patron of this very painting, Sir Christopher Hatton. Would Hatton have left a clue to any of this in the work itself? Very likely yes.

Sir Christopher Hatton.

The Gathering

In this context, one of the most entertaining features of the composition is the small gathering of gentlemen in the upper right. These are distinguished by their clothing and halberds (combined spear and battleaxe) as being of the Queen’s Guard. Hatton, a favourite courtier at the time (and perhaps a little more than that – who knows?) was captain of the Yeomen of the Guard. He was also Vice-Chamberlain. Thus, he was responsible with both the Queen’s safety and personal welfare at all times.

I like that little group of men. It shows us a glimpse into the pomp, and perhaps not a little of the pomposity also, of the daily court landscape. You can almost hear the voices, terribly urbane and perhaps rather overbearing and loud, as well. Peacocks of men, vying for attention constantly within a universe ruled by a single woman. All doublets and legs to the fore (Elizabeth was very fond of legs) and wearing those impossible tights!

But where is Hatton? Well, if we look very, very closely, we might just be able to distinguish his emblem of the white hind on the livery of what seems to be a young page nearby. The page is accompanying a man who might well be Sir Christopher himself. He, alone, appears to be looking in the direction of the Queen as she walks away.

Want to support this blog? It's easy. Buy a book.

~~ HERE ARE THE BOOKS ~~

The Sieve – a practical instrument

But naturally, for all the intricacy and sophistication of the symbolism, it is the unlikely object of the sieve itself that we always return to when we look at this work. The various inscriptions scattered about the painting, moreover, add further layers of significance to its presence. And its mystery. A humble sieve is not something a Queen would be familiar with on a day-to-day basis. It is a practical piece of equipment used by gardeners and bakers to separate the finer elements of a substance from the coarse. Of soil or flour, for example. Separating that which is desirable and useful from that which is merely waste.

Close-up of the sieve itself.

Inscriptions in the Sieve Portrait

Thus, around the rim of the sieve, we can read the inscription:

A TERRA ILBEN / AL DIMORA IN SELLA'

Translated, this means ‘The good falls to the ground while the bad remains in the saddle.’ So it is not just flour or soil we are considering here. It is a kind of sieve of human quality that we are being presented with. Elizabeth, we are urged to believe, is a creature of discernment and refined tastes. Especially where the good and the bad of human nature are concerned. Would-be suitors take note!

Meanwhile, the globe has its own inscription, one perhaps even more intimidating for any would be lover: TVTTO VEDO ET MOLTO MANCHA. This means ‘I see all and much is lacking.’ You can’t get much plainer than that.

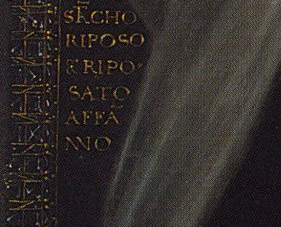

The remaining item of written text worth considering is the actual inscription on the painting itself. Seen to the lower left, this is, again, taken from Petrarch’s story. STANCHO RIPOSO & RIPO SATO AFFA NNO. 'Weary I am and, having rested, still am weary.'

The main inscription on the Sieve Portrait.

A subtle hint

It is telling the world that Elizabeth has possibly had quite enough of all the proposed matrimony nonsense. Any further attempts to exploit her in a dynastic sense (she was by then 50 years of age) should be considered as a pretty futile task. A subtle hint - perhaps not so subtle after all. Rather, a very clear message to all those courtiers and diplomats behind the scenes. Those who still entertained hopes that she would one day make a favourable match with some friendly and useful foreign prince. The kind of match that would secure an heir. Those hopes were now gone.

A moment of realism

The sieve portrait consequently represents a moment of supreme realism. The game is up, Elizabeth is telling us. The real love of her life, Robert Dudley, had long since abandoned the chase. He had already married the Countess of Essex. The recent courtship by Alencon, who had stayed at court for months, all to no avail, had been the last realistic chance of a fruitful marriage. And although the proposal had been put on ice rather than completely abandoned, the situation described in this painting really could not be much clearer. Enough with all this marriage nonsense! It is time to seriously embrace the idea of being the Virgin Queen. And permanently.

And that, of course, is how we will always see her. This fabulous painting marks a vital turning point in history. A reality check. England’s greatest monarch has finally consolidated her public image for generations to come.