The Pied Piper of Hamelin

5th September 2019

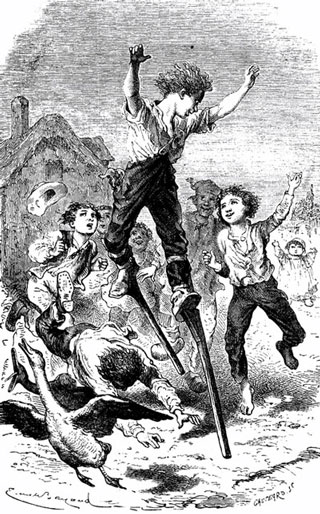

It was a hot summer’s day, and I - a small boy in the company of my parents - was enjoying a week by the seaside when along the beach came a gigantic man on stilts, all colourfully dressed and with a whole procession of children following. It transpired that he was advertising a Punch and Judy show – and naturally, having never seen anything like that before, I got up and followed, too, while my parents dozed in the sunshine.

Book illustration - Ferdinand Hirt & Sohn, Leipzig 1874. You see: anyone on stilts just has to be followed!

The punch and Judy show was not much to my liking, and I somehow failed to notice that all the other children attending had adults with them. Thus, when the performance came to an end, when the money was all counted and everyone had vanished, I was left alone, tearful and … utterly lost! Fortunately, some kind people took a hold of me after a while and reunited me with my by-then very anxious parents. All's well that ends well. But it was my first brush with the phenomenon of ‘celebrity,' and ever since then I have possessed a certain healthy scepticism of such things.

William Barr, Punch and Judy Show. All right, I know my story wasn't that long ago, but you see what I mean. The man playing the pipes seems to have everybody under his spell. And just look at all those wonderful bonnets!

The Allure of the Outlandish

I wasn’t the first to fall prey to the allure of things out-of-the-ordinary, of course, as the famous tale of the Pied Piper of Hamelin clearly demonstrates. The story harks back to the 13th century when the good burghers of that town, situated in the region of Germany known as Lower Saxony, found themselves in deep trouble with an infestation of rats. They were especially pleased, therefore, when out of the blue came an odd sort of fellow dressed in outlandish colours and claiming to be a rat catcher. He told them he would clear the town of its rodents in no time - the sum agreed for his services being a hefty 1,000 guilders.

From Robert Browning's poem The Pied Piper of Hamelin

Illustration by the inimitable Arthur Rackham (1867-1939) for an edition of Robert Browning's poem. The burghers are interviewing the Piper and agreeing terms. Do you think they really mean to keep their side of the bargain?

The burghers, desperate for a solution, promptly agreed - at which the man began playing his magical pipe and the town's entire population of rats, strangely mesmerized by the sound, began to gather and follow him. Still playing, the peculiar man continued to march the unfortunate creatures down to the nearby river Wese where they all waded in after him and drowned.

The pier does his stuff, and the rats pour out of every doorway and follow. Illustration from an old postcard of Hamelin, 1904.

Betrayal and Revenge

Rodent problem solved. Unfortunately, the greedy burghers decided on reflection that the original fee of 1000 guilders had been far too extravagant and they offered the piper a measly 50 guilders instead for his trouble. Furious at the betrayal, the rat catcher refused to accept such an insult and left the town.

It seemed at first he would not trouble them any further, but one day he did return while all the adults were at church service. Playing his magic pipe once again, he drew towards him all the children of the town this time - 130 in number - who were enchanted by his melodies and proceeded to follow him. Still playing, he led them away to a great opening that had appeared in the nearby mountainside, into which they all vanished, never to be seen again.

A nonchalant piper leads the youngsters away in this colourful illustration by Kate Greenaway for an 1887 illustrated edition of Browning's poem. The printing was achieved through wood-block engraving, made by Edmund Evans (1826-1905) who collaborated with Greenaway on a number of projects of this kind.

A Source of Inspiration

Clearly, for the people of Hamelin it was a disaster. An entire generation and all their hopes for the future had been lost - all apart from one little chap, that is, who was lame and had not been able to keep up with the others, and (some sources say) one more who was deaf and so had not been influenced by the piper and one who was blind and could not see where to go. It was they who recounted what had happened. A Gothic legend was born 'Der Rattenfänger von Hameln.’ And in the 14th Century, a stained glass window was produced for the local church to commemorate the event (destroyed, alas, in 1660). The tale has been a source of inspiration to artists ever since.

In Germany, the Romantic poet Goethe wrote about it, and the Brothers Grimm made it into one of their most well-known fairy tales. Meanwhile, our own Robert Browning in Victorian England wrote verses describing the event which, as you can see, also inspired a lot of excellent artwork. Examples of some of the most striking are included here, beginning with this fabulous example by James Elder Christie:

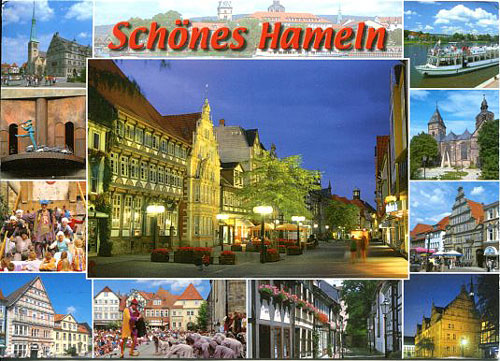

In our own times, the legend has continued to capture the imagination of artists, film makers, poets and composers. And to this day the people of Hamelin, and the tourist department of that town in particular, still insist that the story is based on fact. It remains a great draw for visitors. In the town itself you will find statues of the Piper. Every Sunday in summer, local players re-enact the tale - while music or dancing of any kind is still prohibitted in the Bungelosenstrasse ("street without drums") – this being the last spot that the unfortunate youngsters were reported to have been seen on that fateful day all those centuries ago.

The drama and sense of frenzied movement in this pastel drawing by Elizabeth Adela Stanhope Forbes (1849-1912) really is amazing. Housed in the Penlee House Gallery & Museum, Cornwall. There's really no turning back now for the doomed procession. Faster, faster!

Metaphors and Symbols

Meanwhile, historians still debate as to whether the tale might really have just been allegorical - referring, for instance, to a migration of young people away from the area, or to some terrible disease such as the plague (even though the original story predates the plague times in that part of the world). The wider symbolism of the subject has, of course, rarely gone unnoticed – becoming a kind of dance macabre in which innocent young people are exploited or led astray by those in positions of power. An easy enough analogy.

This extraordinarily colourful and intense mural painting by Maxfield-Parrish from 1909 can be seen in the Pied Piper Bar of the Palace Hotel in San Francisco.

Detail of the Piper himself - and with everyone in such a hurry.

The rocky mountainside is no hindrance. Such enthusiasm!

Celebrity

Perhaps we can even view it as a persuasive metaphor on the perils of celebrity: of how we are fascinated by the beauty or eccentricity of certain specially endowed individuals until we eventually become totally beguiled by them, even to the extent of believing they have some special insight into reality that might be worth obeying. It also suggests that celebrity itself is invariably short-lived and often controlled by others – the good burghers of society whoever or whether they might be, pulling the strings from behind the scenes.

Finishing with perhaps the most chilling of all: an 1868 woodcut engraving attributed to Henry Marsh after artist John La Farge. There is no malice in the face of the Piper. No deliberation or even much joy at all on the faces of the victims. A great wind of circumstance and inevitability is simply blowing them away.

Conclusion

Thus, the Pied Piper becomes ultimately a story of betrayal and vulnerability as much as one of retribution and revenge. It also serves as a salutary reminder that cheating has consequences far beyond the present moment. And that the innocent can suffer those consequences every bit as much as those who are guilty.

And so, Ladies and Gentlemen, I give you The Pied Piper! It really has everything as far as stories go, don't you think? And of course it is a true story. It really did happen. You just ask the good burghers of Hamelin.

You might also like

Pre-Raphaelite

Gothic Art

Victoria

Historical Novel