Rude eyes

The irrational, inspirational part of us does not always integrate easily with the demands of the real physical world. And the arts and sciences have always appeared in contention for possession of the human intellect. But both are valid, and both are essential for our well being and balance: something we sometimes forget at our peril. And even though the astronomers have been coaxing us away from the poetic side towards a more rational perspective of the cosmos for centuries, not everyone has been willing to go quietly. Or, as Oscar Wilde declared in his 1881 poem The Garden of Eros:

‘Shall I, the last Endymion, lose all hope,

Because rude eyes peer at my mistress through a telescope!’

'Um … it's that lovely Selene again, I see. Excellent.'

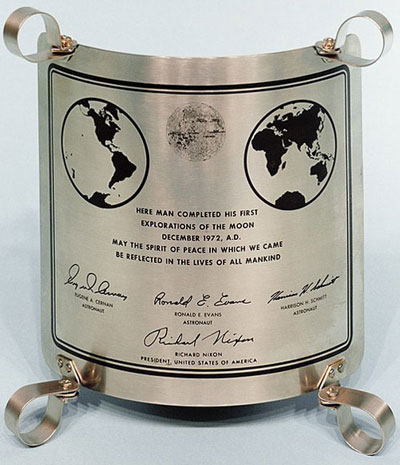

A good question even for us today 118 years after Wilde’s passing - because by 1969 there were not only rude eyes gazing at his mistress but men trampling all over her in spacesuits as well. Except that it wasn't quite the same moon, was it? One was the real moon, the physical place, the other was the moon of ideas. We can, if we choose, decide for ourselves which is the most relevant. Ideas are for keeps, and many of the most important of them span the fickle generations as they come and go. Our moon is one of them.